Opening Scene

The Moment the Timeline Breaks

By the time anyone realised the timeline had broken, the project was already too far gone. The platform that was meant to take six months had stretched well past a year. The prototype looked promising on paper, but the real delivery work, the integrations, the approvals, the rewrites, the architecture debates, had taken on a life of its own. Every week introduced a new delay. A dependency no one owned. A security review waiting for a slot. A legacy system needing a fix before anything else could move.

No one could say when the platform would be ready. But everyone sensed the finish line had drifted somewhere out of sight.

This story plays out inside enterprises every year. It is not a reflection of weak engineering. It is the predictable outcome of asking internal teams to build at commercial speed inside environments designed for stability, governance and continuity. It is the quiet gap, the one between ambition and operational reality, that defines the build-vs-buy conversation far more than technology ever will.

Why internal builds slow down before they speed up

Organisations rarely fail because they lack the ability to write software. They fail because the environment surrounding that software multiplies every estimate.

Across industries, the same patterns appear.

1. The organisation moves slower than the vision

External vendors are built for delivery. Internal teams are built for resilience.

Those two worldviews collide the moment the first dependency emerges. Internal engineering velocity is shaped not by talent, but by competing priorities, architectural debt, shared backlogs, and governance frameworks that ensure safety but slow momentum.

A four-week prototype can become a four-quarter delivery cycle once approvals, testing and integration gates appear.

2. Capacity is always smaller than the estimate

Building isn't just engineering. It's:

- QA

- DevOps

- security

- data modelling

- UX

- product ownership

- documentation

- long-term maintenance

Buying includes these things. Building means creating them.

Most organisations believe they have the people. Few have the capacity, and capacity, not talent, determines how long a build will take.

3. Context switching is the invisible tax

Internal teams rarely work on one transformation at a time. They support BAU, handle incidents, navigate audits, fix architectural debt, and respond to requests from across the business.

Each interruption seems small. Together, they quietly erode the project's forward momentum.

4. Dependency chains turn milestones into waiting rooms

A vendor controls its own pipeline. An enterprise build depends on other teams whose priorities lie elsewhere.

Security approvals wait for a backlog slot. Data access needs governance sign-off. Architecture committees meet monthly. Legacy knowledge sits with a team already overstretched.

These aren't delays, they are the operating reality.

Why internal teams struggle to keep pace with commercial expectations

Commercial delivery benefits from three freedoms internal teams rarely enjoy:

- Dedicated focus: not split across BAU.

- Clear scope: not reshaped weekly by stakeholders.

- Single accountability: not shared across multiple departments.

Vendors can say no. Internal teams cannot.

So the work expands. The momentum slows. The timeline stretches until it bears no resemblance to the plan that started it.

The real build-vs-buy question

Most organisations evaluate build-vs-buy on technical grounds:

Does the platform fit our architecture? Can we customise it? Is the roadmap compatible with our needs?

But the real question is operational:

Do we have the capability, the capacity, and the continuity to build and sustain this product for the next decade?

Capability

Do the required skills exist today, not aspirationally, not through future hiring, but now?

Capacity

Can these people do the work without compromising BAU?

If capacity isn't protected, the timeline will slip. Always.

Continuity

Can we own the platform long after launch?

Ownership means:

- maintenance

- security

- release cycles

- architectural evolution

- reliance on tribal knowledge

- permanent support overhead

Most organisations plan for the build. Few plan for the ongoing responsibility.

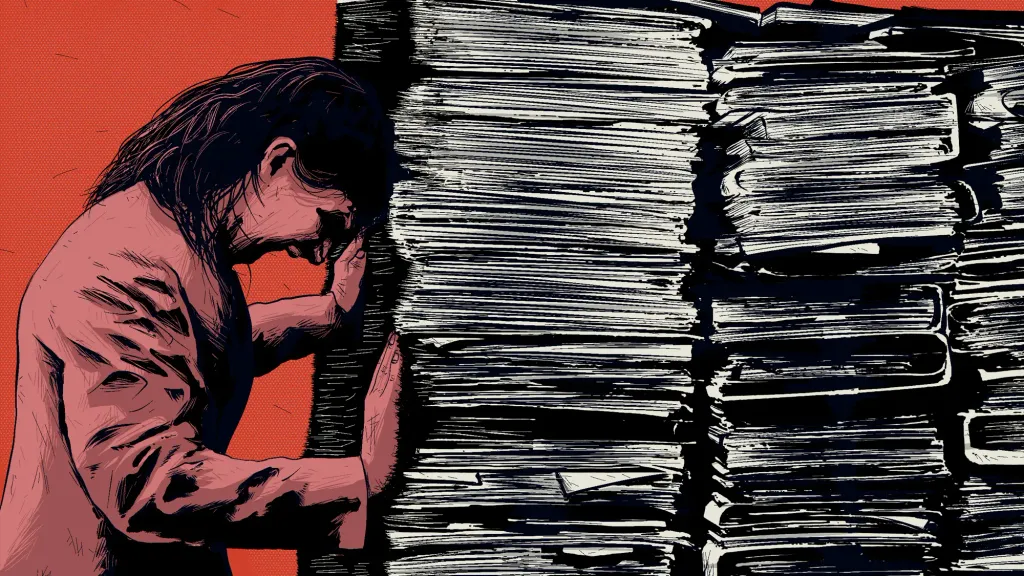

The human impact

Behind every delayed build is a tired team. Not because they can't deliver, but because they're delivering everything else at the same time.

They are pulled between urgent incidents and strategic work. Between leadership updates and undocumented legacy systems. Between the promise of transformation and the gravity of BAU.

It is not failure. It is context.

The shift: build-vs-buy as governance, not procurement

Digital transformation doesn't fail at the keyboard. It fails in the spaces between teams, in the processes, the approvals, the dependencies, the capacity gaps and the quiet friction that turns weeks into quarters.

Buying isn't a weakness. Building isn't a badge of honour.

The right choice is the one aligned to the organisation's operational reality, not its strategic aspiration.

Those who recognise this early will deliver faster, more sustainably, and with far less strain on their teams.

Because success doesn't belong to those who build the most. It belongs to those who build where it makes sense, and buy where it doesn't.